Our survey of Americans with disabilities revealed that:

Our survey of Americans with disabilities revealed that:

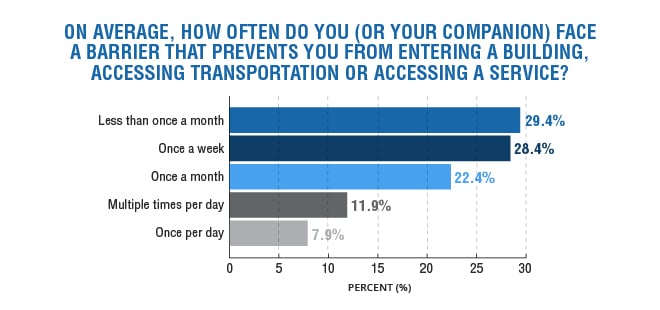

- 28% encounter a barrier to a building, transportation or service once a week

- 20% encounter a barrier at least once a day

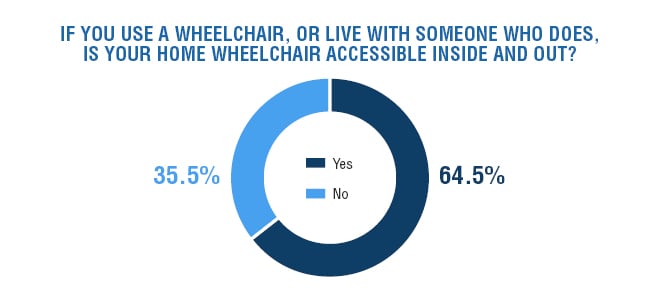

- 36% live in a home that is not wheelchair accessible; of this group:

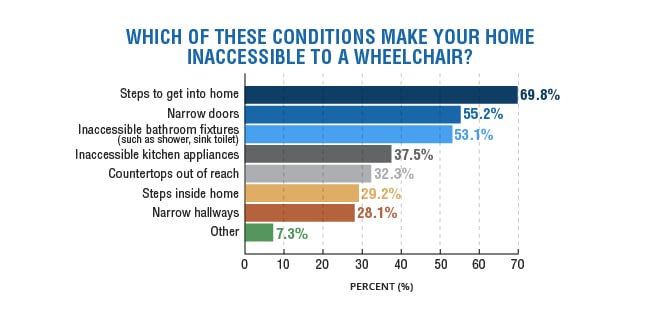

- 70% have steps leading into the home

- 51% cannot afford to make their homes wheelchair accessible

- 25% say they find ways to “deal with” the challenges and inconveniences

- 16% say that landlord/homeowner/condo board won’t allow modifications

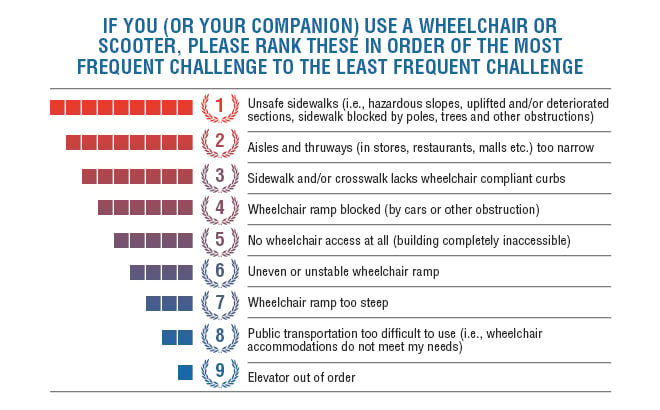

Top 5 challenges to wheelchair/scooter users:

- Unsafe sidewalks due to hazardous slopes, uplifted/deteriorated/blocked sections of sidewalk.

- Narrow aisles/thruways in public places

- Non-compliant curbs and crosswalks

- Blocked wheelchair ramps

- Buildings that are completely inaccessible

In January 1987, Robert L. Burgdorf Jr. drafted the The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) as “a response to an appalling problem: widespread, systemic, inhumane discrimination against people with disabilities.” On July 26, 1990 the bill that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation, and all public and private places that are open to the general public was signed into law. The purpose of the law is to make sure that people with disabilities have the same rights and opportunities as everyone else. Problem solved, right? Not exactly.

In March 2017, we surveyed 554 Americans with disabilities (including people who live with or are companions to people with disabilities). The provisions of the ADA have effectively removed many barriers, but our survey revealed that far too many still remain.

Barriers Everywhere

Americans with disabilities often encounter barriers that prevent them from entering a building, accessing transportation or accessing a service. 28% of survey respondents say that, on average, they encounter a barrier once per week. 12% say it happens multiple times per day!

What Gets in the Way?

What Gets in the Way?

Those who depend on a wheelchair or scooter (or accompany someone who does) were asked to rank a list of common barriers and obstacles that prevent them from entering a building, accessing transportation or accessing a service in order of the most frequent challenge to the least frequent challenge. The #1 complaint: Unsafe sidewalks due to things like hazardous slopes, uplifted and/or deteriorated sections and sections of sidewalk blocked by poles, trees and other obstructions.

Crumbling sidewalks and roads are a common sight in many communities. In 2015, the city of Los Angeles agreed to fix a huge backlog of crumbling, impassable sidewalks and remove other barriers that prevented wheelchair access–a violation of the ADA. The L.A. City Council took this action only after attorneys for the disabled filed a lawsuit.

At Home, You’re On Your Own

36% of our survey respondents who depend on a wheelchair or scooter, or live with someone who does, say that their home is not wheelchair accessible.

70% face a huge hurdle before they can even enter their homes: STEPS! Once inside, 55% say narrow doors impede their ability to maneuver around the home. 53% are inconvenienced by inaccessible bathroom fixtures.

What’s the Big Deal?

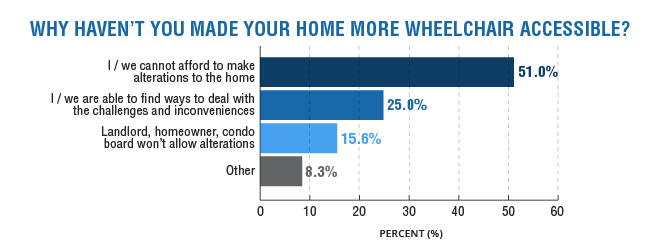

Why wouldn’t a person who needs a wheelchair or scooter simply renovate his or her home to make it completely wheelchair accessible? The #1 reason: money.

51% of survey respondents say they can’t afford to make alterations to their homes. While some federal and state organizations and private non-profit charities offer grants to subsidize remodeling costs, Americans who depend on a wheelchair or scooter are typically responsible for the costs associated with modifying their homes, even those who live in a rental property.

Many of the 25% who say they find ways to deal with the challenges and inconveniences of living in a home that is not wheelchair accessible certainly have a reduced ability to live independently or even spend time alone. When the challenge is a flight of steps, assistance from one (preferably two) people is required, which adds another challenge: finding people who are ready, able and willing to assist whenever needed.

Define “Reasonable”

Under the ADA and the Fair Housing Act, Americans who have a disability, can ask for a reasonable accommodation for that disability.

16% of our survey respondents say that they haven’t made their home wheelchair accessible because a landlord/homeowner or condo board won’t allow them to make alterations to the home.

According to this joint statement by the US Department of Justice and the Department of Housing and Urban Development: “A request for a reasonable accommodation may be denied if providing the accommodation is not reasonable – i.e., if it would impose an undue financial and administrative burden on the housing provider or it would fundamentally alter the nature of the provider’s operations. The determination of undue financial and administrative burden must be made on a case-by-case basis involving various factors, such as the cost of the requested accommodation, the financial resources of the provider, the benefits that the accommodation would provide to the requester, and the availability of alternative accommodations that would effectively meet the requester’s disability-related needs.”

Try to make sense of that.

Willful Disregard for the Law

The ADA guarantees protections to people with disabilities but too often, rules are broken, provisions ignored and ambiguities exploited without consequence to anyone but the people with disabilities.

Essentially, a landlord or anyone who has authority over the property can use the “undue burden” clause to deny a request for accommodations. The person with a disability can file a Fair Housing Act complaint to challenge that decision and in the meantime endure barriers that may be in violation of the law.

“New York Has a Great Subway, if You’re Not in a Wheelchair” writes Sasha Blair-Goldensohn in a March 2017 “New York Times” opinion piece. After an accident eight years ago, the lifelong New Yorker found himself dependent on a wheelchair and “became increasingly aware of how large, inflexible bureaucracies with a ‘good enough’ approach to infrastructure and services can disenfranchise citizens with disabilities, many of whom cannot bridge these gaps on their own.”

Joyce Forrest, a Washington DC resident, risks her life everyday just to travel to her bus stop in her wheelchair. Matt Trott of Falls Church, VA, one of the wealthiest counties in Virginia, faces similar obstacles. Like many wheelchair users, they suffer tremendous inconveniences and dangers, and they do not have the same opportunities as everyone else, but local officials do nothing. Apparently, it takes a lawsuit or a news team to get government officials to look into the problems. Not fix, look into.

Too often, people with disabilities have to fight long and hard for the rights and protections afforded under the ADA.